Instructions:

Please click on the play button at the top of the page to hear the narration and then follow the directions at the bottom of the page. All other locations will auto play.

"As Aix belonged to Cezanne and Marseilles to Monticelli, Van Gogh fixed his choice -- for unknown reasons -- on Arles."

Biographer Jean Leymarie

Vincent Van Gogh arrived in Arles in February 1888 after a snowfall. Much of what excited Van Gogh about Arles is present today in its people, parks, countryside, river banks, narrow streets, night cafes and Roman past.

In his own words:

But here in Arles the country appears flat. I saw some magnificent red terrain planted with grapevines, with a background of mountains of the most delicate lilac. And the landscapes in the snow, with the summits white against a sky as luminous as the snow, were just like winter landscapes done by the Japanese.

Van Gogh arrived in Arles with great hope and need for renewal. Arles became pivotal in his artistic life -- he produced more than 300 paintings and sketches here -- and pivotal in other ways as the story of Van Gogh in Arles plays out on this tour.

The story of Vincent Van Gogh in Arles is told primarily through his own words, expressed mostly in letters to his brother, Theo. We provide both an extract from Van Gogh's letter and a link to the complete letter and a link back. We also use his paintings and our own photographs to highlight points of interest.

There are two ways to use this app-guided walking tour.

Option One: You can just wander around Arles. The map will show you where you are in relationship to points of interest. Click on the 'Show Map' button and click on 'My Location' to see where you are. You must be out of doors and you must allow the application to detect your location.

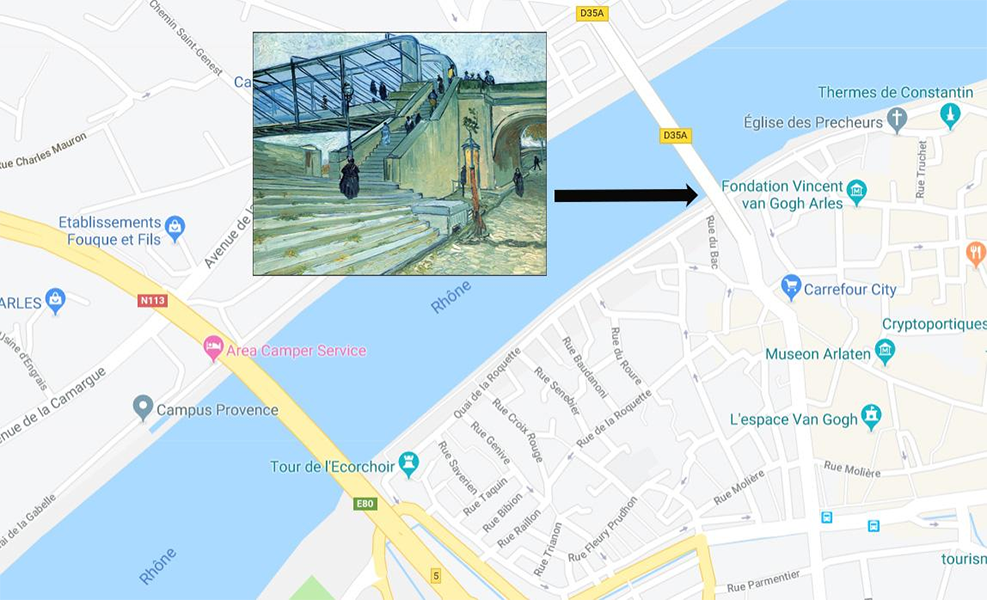

Option Two (recommended): You can follow directions from point to point. To begin the guided walking tour of Van Gogh's Arles, head to the Rhône River and to the Trinquetaille Bridge. This is the smaller of the two bridges that cross the Rhône River from Arles. The map and image will help you identify the starting point. You'll know that you found the starting point if you found the panel that displays Van Gogh's painting, Trinquetaille Bridge.

Important Tip for both Options: Click on the 'Show Map Button' and then on the 'My Location' button to see where you are in relationship to the tour stop. Always use caution when walking and using the map.

Lastly: At each location, you'll see directions to the next location at the bottom of the page. These won't be narrated. Simply scroll toward the bottom of the screen to see step by step directions. Good luck.

ver 1.9

© 2020 LodeStar Learning Corporation

Web Version Shared under Creative Commons License -- Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs

CC BY-NC-ND

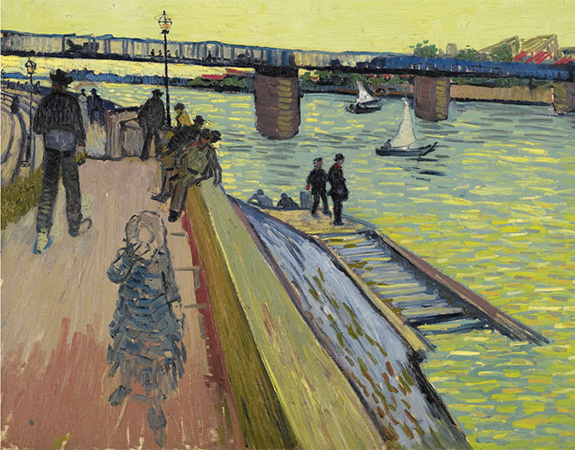

You are standing before the Trinquetaille Bridge, subject of several of Van Gogh's paintings and sketches. The bridge to the Trinquetaille area of Arles crosses one of the branches of the Rhône. The Rhône River is more than 500 miles long, starting in the Swiss Alps and flowing into the Mediterranean Sea. The Rhône forks into two branches just upstream of Arles, forming the Camargue delta. Arles was an important port city along the river's way, but by Van Gogh's time, the port city had significantly quieted down as a result of the railroad.

Of Trinquetaille, Van Gogh wrote:

Well, let's be of good heart, and not despair. I hope to send you this attempt along with some others soon. I have a view of the Rhône - the iron bridge at Trinquetaille - in which the sky and the river are the colour of absinthe; the quays, a shade of lilac; the figures leaning on their elbows on the parapet, blackish; the iron bridge, an intense blue, with a note of vivid orange in the blue background, and a note of intense malachite green. Another very crude effort, and yet I am trying to get at something utterly heartbroken and therefore utterly heartbreaking.

Nothing from Gauguin. I certainly hope to get your letter tomorrow. Forgive my carelessness. A handshake.

Van Gogh hoped Paul Gauguin would join him in Arles. Paul Gauguin, a French post-impressionist painter, was currently in Brittany in the north of France. He had returned from Martinique ill and destitute. Theo Van Gogh, Vincent's younger brother, was an art dealer in Paris. He purchased and exhibited several of Paul Gauguin's works. In return, Theo pressed Gauguin to join Vincent in Arles. Our tour will eventually bring you to the location of the Yellow House -- the house that Vincent prepared in anticipation of Gauguin's arrival.

With the Rhône river on your left, follow the river road under the bridge (Quai Marx Domoy) to Rue du Docteur Fanton Turn right. Always be careful as you walk along the road. You might spot the red sign pointing to Fondation Vincent Van Gogh. If you get lost, you will see other signs that guide you to our tour spot.

Again, use the 'Show Map' button and 'My Location' to help you.

As you walk down Rue du Docteur Fanton, in a couple of blocks, you will veer to your left. You will know when to veer when you see the front wall of Fondation Vincent Van Gogh.

You are looking for this:

The modern entrance of the Fondation Vincent Van Gogh merges with the Hôtel Léautaud de Donines, a fortified home, built in the 15th century by a merchant. Not understanding its mission, many people have expressed their disappointment in the Fondation because of the few Van Gogh paintings housed here. But the Foundation was created to serve as a launch point for artistic and cultural activities inspired by Van Gogh and his time in Arles.

Van Gogh came to Arles to establish a center for artistic expression, to be headed, as he envisioned it, by Paul Gauguin. Van Gogh dreamed of founding a home in Arles for struggling artists, for 'the poor cab horses of Paris'.

Here I am seeing new things, I am learning, and if I take it easy, my body doesn't refuse to function.

For many reasons I should like to establish some sort of little retreat, where the poor cab horses of Paris - that is yourself and several of our friends, the poor impressionists - could go out to pasture when they get too exhausted.

If the Fondation is featuring an artist of interest to you, please visit, otherwise let's continue our walking tour of Arles where Van Gogh will be found not so much on the walls of a museum but in the people, the streets and gardens and river banks of this amazing city.

When you leave Fondation Vincent Van Gogh, keep following Rue du Docteur Fanton all the way to Rue de Suisses. You can check your location on the map and you can check for building signs that say Rue du Docteur Fanton. If you have a good sense of direction, the Rhone river will be on your left, but you won't be able to see it.

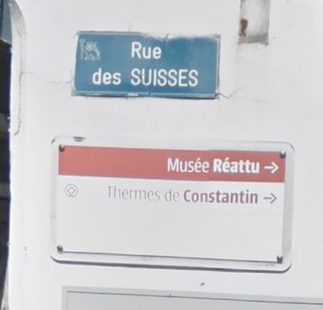

You will know that you have traveled the length of Rue du Docteur Fanton (about a 1/10 of a mile) once you see the Musee Reattu and the Rue de Suisses signs on the corner of a building. This leg of the journey is rather serpentine. If you get lost, just follow signs to either Musee Reattu or the Hotel Musee. These places are about a block from the river.

Follow Rue de Suisses for about a block to Rue Reattu. Follow Rue Reattu to the Rue du Grand Prieuré. Look for the red door. Turn left.

You will first come up to the Hotel Musee.

You are looking for this:

Hôtel du Musée is just one example out of many affordable but charming Arlesian hotels in this area. This hotel captures both the spirit of art through its decor and small exhibition of local artists and the city's long history. The hotel was built in the 16th century and features two lovely open patios. (Incidently, we have no connection to the hotel or any other establishment in Arles.)

In contrast to what we might pay for a night's lodging as visitors to Arles, Van Gogh's rent in the Yellow House was 15 francs per month. We know this fact from his letter to Theo.

Theo entirely supported his brother in his artistic pursuit. He sent an allowance that Vincent used for food, lodging, and artistic supplies like paint and canvasses. Sometimes, Theo would send a larger sum for special projects -- like the furnishing of the Yellow House.

Continue another 100 feet along Rue du Grand Prieuré to the Musee Reattu.

You are looking for this:

Musée Réattu housed the Catholic order of Malta until the 18th century. The building was then acquired in stages by the French painter Jacques Réattu, who preceded Van Gogh by nearly a century and whose work, life, schooling and residence stand in sharp contrast to that of Van Gogh.

The Réattu museum houses nothing of Van Gogh other than a handwritten letter addressed to Paul Gauguin in January,1889. In fact, very little remains of Van Gogh's artwork in the city of Arles -- although the source of his inspiration is very much present today in the city, in the Provençal countryside, and in Saint Remy, as it was in 1888.

From the Réattu museum, one can also discover the attachment that Pablo Picasso had for Arles. He bequeathed to the museum a series of drawings. Picasso was attracted to Arles by the bullfights in the Roman amphitheater and by the work of Van Gogh who died a couple of decades before Picasso first painted in this city.

Picasso exhibited in Réattu in 1957. He died in 1973 in Mougins in southeastern France.

An extract of the letter from Van Gogh to Gauguin, exhibited in the Réattu:

My dear friend Gauguin,

Thank you for your letter. Left behind alone on board my little yellow house - as it was perhaps my duty anyway to be the last to leave - I am not a little put out at my friends' departure.

In this letter we can see a hint of things to come. Paul Gauguin did join Van Gogh in Arles. But Gauguin's subsequent departure would be a turning point in Van Gogh's emotional well-being.

Continue walking along Rue du Grand Prieuré in the opposite direction of Hotel Musee. Your goal is to wind around to the river side of Musee Reattu. You'll find stairs that get up to the walkway along the river.

You'll pass the Baths of Constantin, which date back to the fourth century, part of the palace of the Roman emperor Constantine. A lot of the ruin is visible from the outside.

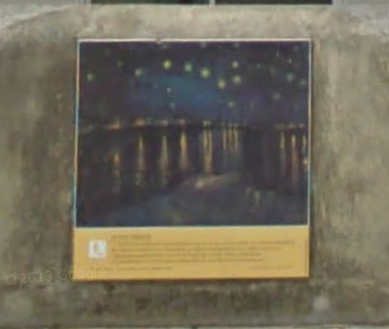

Once you've made it to the river, keep the river to your left and walk up river along the Quai Marx Dormoy until you see the panel of Van Gogh's Starry Night over the Rhone. The distance is a 1/4 of a mile. The panel is against the wall. If you pass the row of angled parking spots for busses, you have gone too far.

You are looking for this:

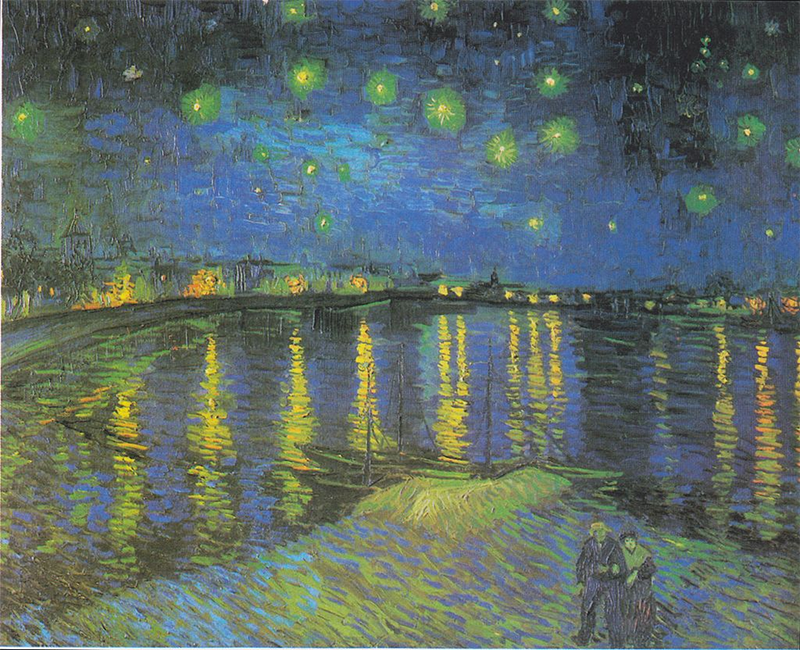

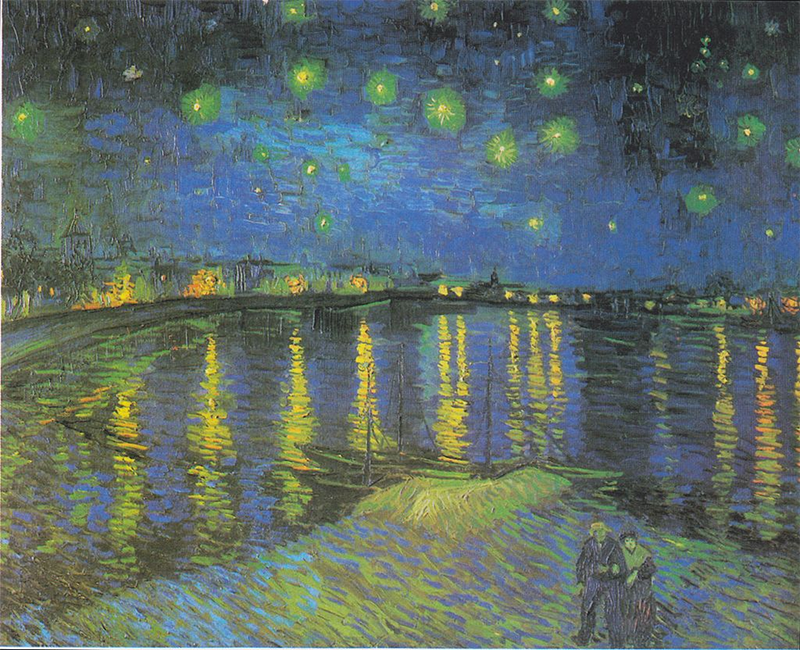

Van Gogh found the night to be as alive and richly colored as the day. The time of the year was the fall equinox and Van Gogh stood on this spot and captured in his imagination the energy of the autumn night sky. He referred to the painting as 'Starry Night', similar to the name he ascribed to his most famous painting, 'The Starry Night', which was painted circa June 1889 in Saint Remy, where he was hospitalized. Today, as you can see, river cruise boats have replaced the fishing boats depicted in the painting of the Rhone. A size 30 canvas would be 72.5 cm × 92 cm or 28.5 in × 36.2 in, a French standard.

Included a small sketch of a 30 square canvas - in short the starry sky painted by night, actually under a gas jet. The sky is aquamarine, the water is royal blue, the ground is mauve. The town is blue and purple. The gas is yellow and the reflections are russet gold descending down to green-bronze. On the aquamarine field of the sky the Great Bear is a sparkling green and pink, whose discreet paleness contrasts with the brutal gold of the gas. Two colourful figurines of lovers in the foreground.

From here you need to head away from the river along Rue de la Martin. When you've reached the park (north end of the Larmartine circle), head straight across the park. The Yellow House is on the far corner to your left. The panel is on your right on the paved walkway on the far side of the park. La Maison Jaune marked on the map below is the panel that that depicts The Yellow House. We encourage you to stand and view the area from the panel that displays Van Gogh's painting of the Yellow House. As you look north from the panel, you'll be able to see buildings and the bridge that are depicted in the painting. The panel is located on the paver walkway across the street from the house. Again, show your location on the map and we'll help you find this vantage spot.

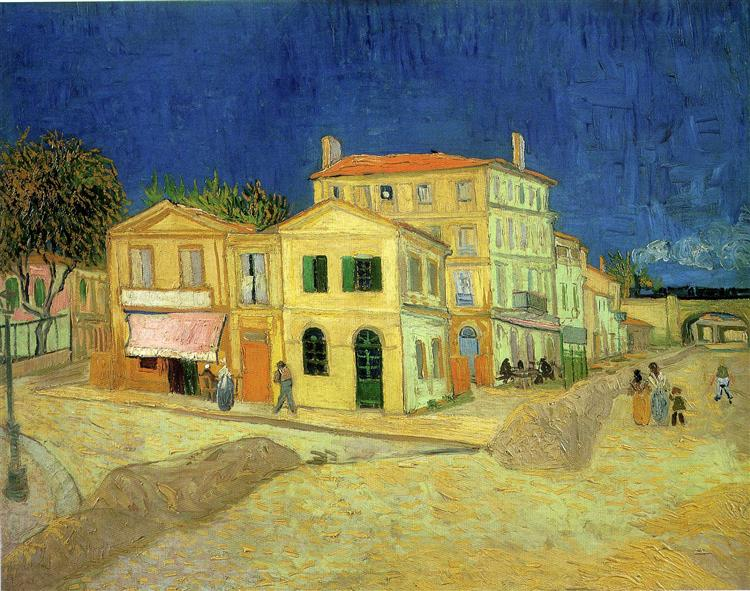

You are looking for this:

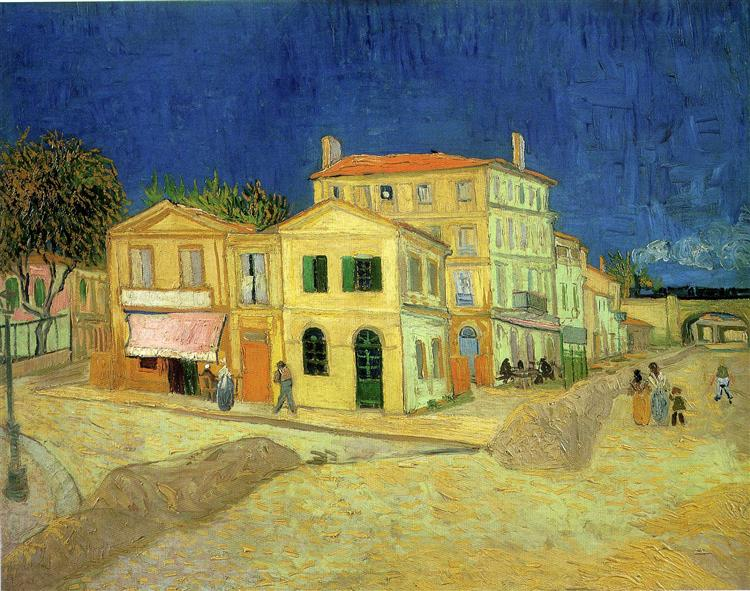

Van Gogh's studio (and later home) as of May, 1888 was the Yellow House that is depicted in his painting. He rented several rooms there and furnished it with great care in anticipation of Paul Gauguin joining him to establish a center for the arts. The building was destroyed in World War Two but standing on this spot you can still see the building that stood immediately behind the house, visible in the painting, as well as the bridge in the background.

My dear Theo,

Thanks for your letter and the 50-fr. note. As you learned from my wire, Gauguin has arrived in good health. He gives me the impression he is even better than me.

Naturally he is very pleased with the sale you have effected, and I no less, since in this way certain expenses absolutely necessary for the installation need not wait, and will not weigh wholly on your shoulders. G. will certainly write you today. He is very, very interesting as a man, and I have every confidence that we shall do loads of things with him. He will probably produce a great deal here, and I hope perhaps I shall too.

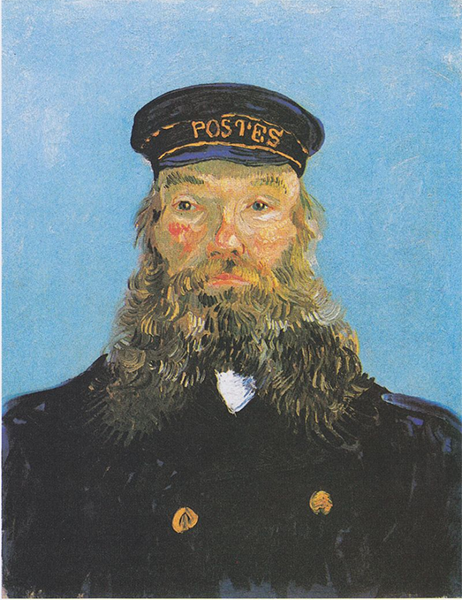

Settled in Arles and in his studio, Van Gogh captured nature and everyday life not as the 'dead-eye' of a camera would see it, he would say -- not objectively - but through his own imagination. He reveled in spring blossoms but also tore into the depths of human despair. Amid all of this creativity, he was befriended by Joseph Roulin, an Arlesienne postman, and Madame Roulin and all of their children. The family represented common decency and humanity -- and they were willing to sit for Vincent, who had very little money to compensate them.

On the south end of Larmartine Circle, look for the old city gates. They are pictured below. Walk through the gates along Rue de Cavalarie, which eventually becomes Rue Voltaire. When you've passed through the gates, we'll tell you more about this area.

You are looking for this:

We're headed toward the Roman Amphitheater and past the neighborhood of the Hotel-Restaurant Carrel, where Van Gogh first lived in Arles. To get there we are following Rue de la Cavalarie and then Rue Voltaire. Parts of Rue Voltaire can be very interesting especially as you approach the amphitheater. Imagine walking the streets of the city as Van Gogh must have done. You'll find old stone buildings dating back to a prosperous 17th century, brightly decorated cafes, iron lamp posts, freshly painted shutters, hanging plants, flowers, tourists and Arlesians.

As you walk toward the Amphitheater, you will come upon Fountain of Amédée Pichot. Keep to the left of the fountain in order to stay on Rue Voltaire. Incidently, Amédée Pichot lived between 1795-1877. He was a doctor, journalist, translator of English literature and lover of letters. The fountain was completed a year before Van Gogh arrived in Arles. But Van Gogh seemed disinterested in monuments.

What really interested Van Gogh? As Jean Leymarie writes:

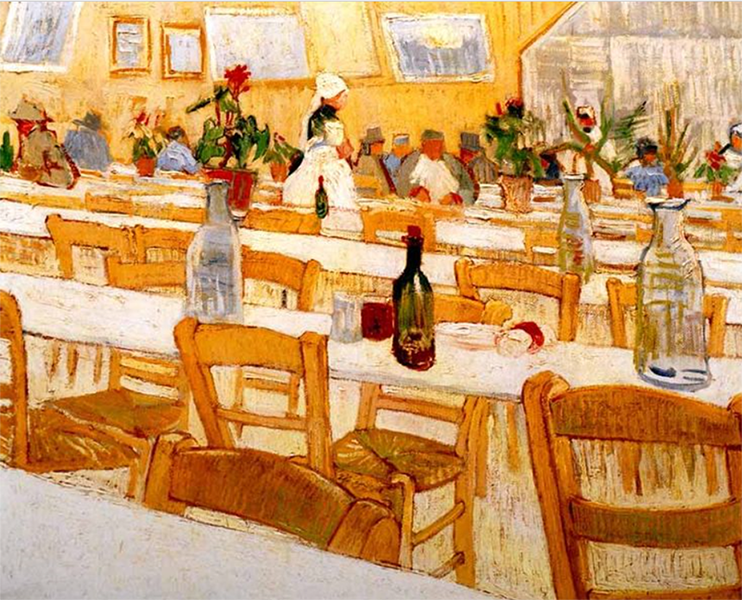

"None of the Roman or medieval monuments interested [Van Gogh], for he was the reverse of an aesthete and went straight to nature and real life. The dreams of the yellow house and the artists' community broke drown tragically. He frequented and painted the haunts of the lonely, the restaurant with vacant tables, the lurid night cafe, the dismal garrison brothel, the hospital grounds."

Walk down Rue de la Cavalarie and then Rue Voltaire for about a 1/10 of a mile total. Once you've walked far enough, we'll jump to a new site. The intersection is Rue Leon Blum. Hotel Voltaire will be on your right and Briocherie de la Chapelle on your left.

You are looking for this:

You are standing near 1 Place Voltaire. If you look to the west, the next intersection (Rue Leon Blum and Rue Amédée Pichot) is near where the Hotel-Restaurant stood. It no longer exists -- but this is the general area where Van Gogh first lived when he arrived In Arles. The streets have been renamed since Van Gogh's time. The present day 30 Rue Cavalerie is not the location of Hotel Carrel.

But Van Gogh complained bitterly about the food at the Hotel-Restaurant as well as the expense and eventually resettled at the Yellow House.So get your blood in good condition in advance; here, with the bad food, it is difficult to pull through, but once one is in good health again it is less difficult to remain so than in Paris. Write to me soon, always the same address: “Restaurant Carrel, Arles.”

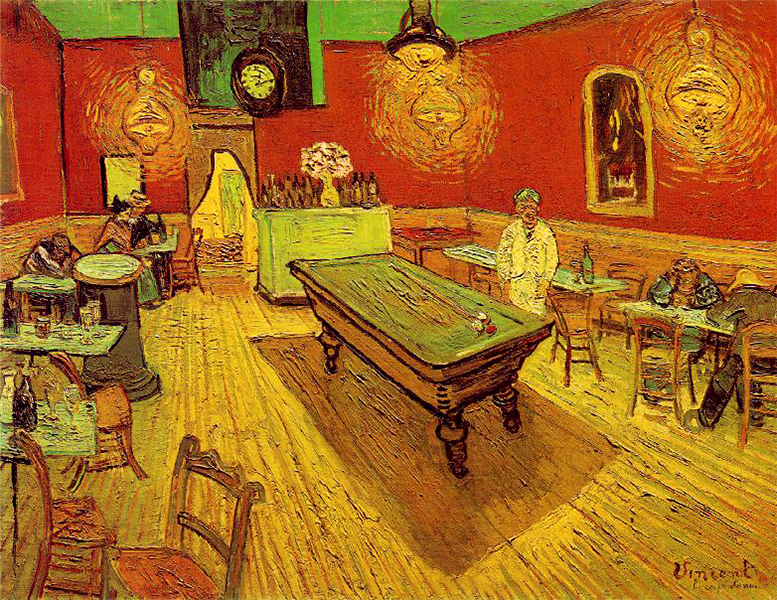

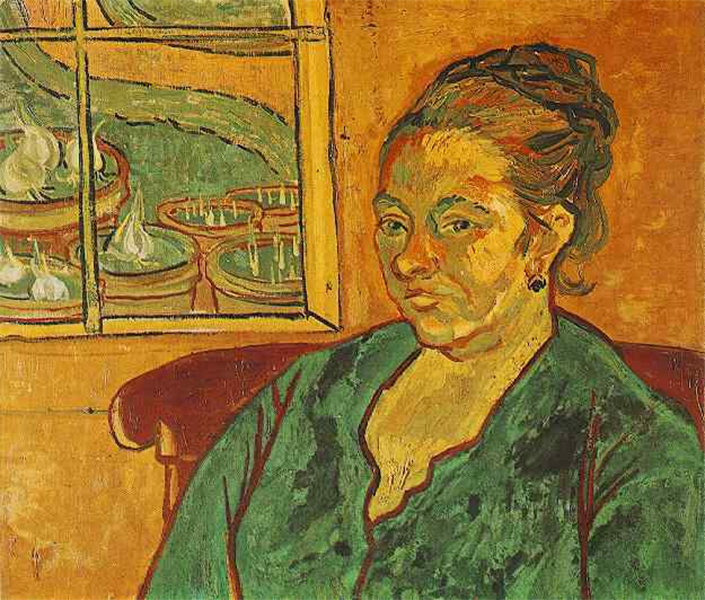

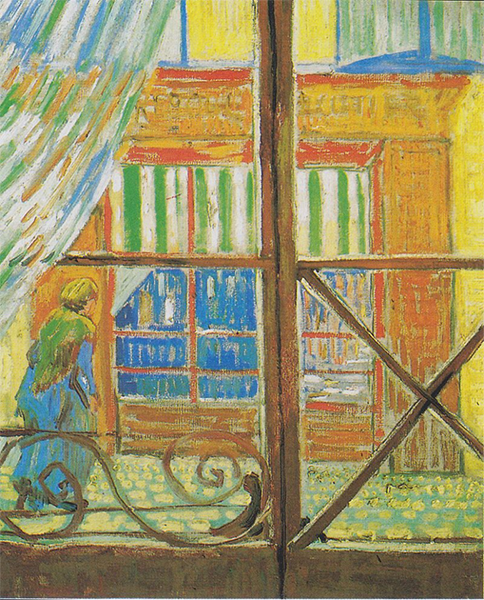

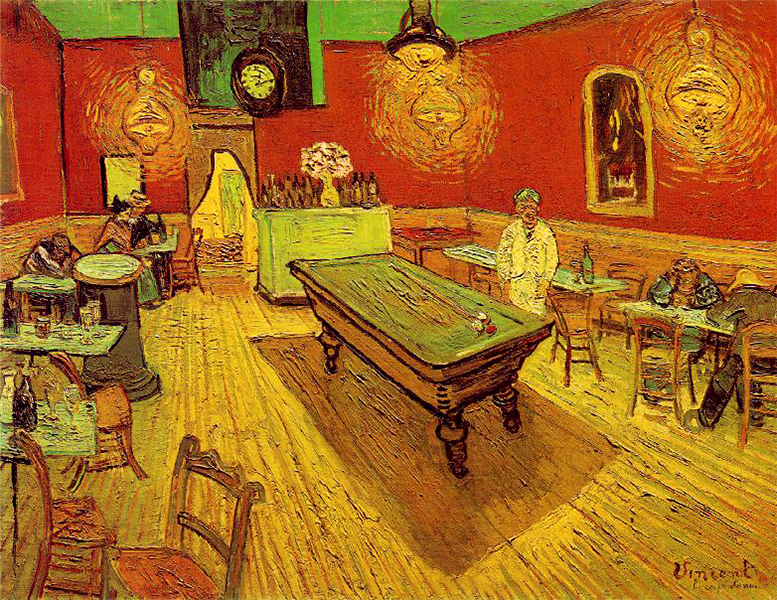

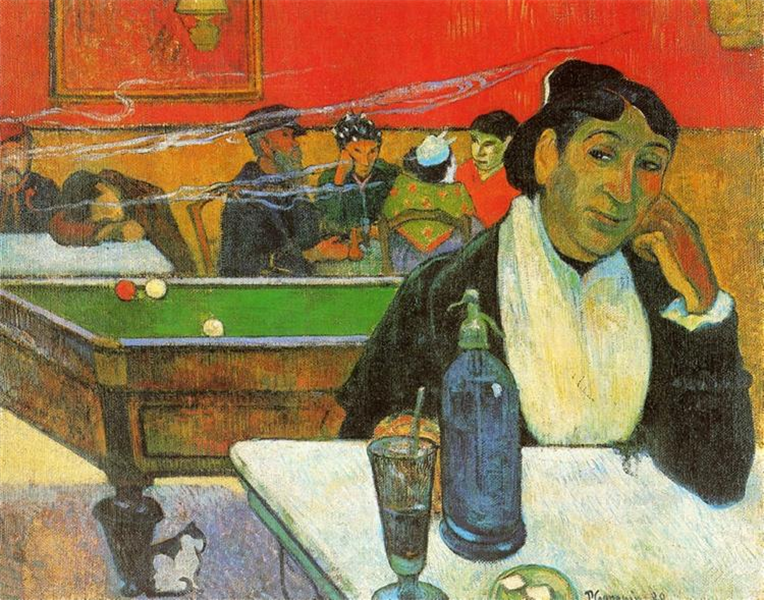

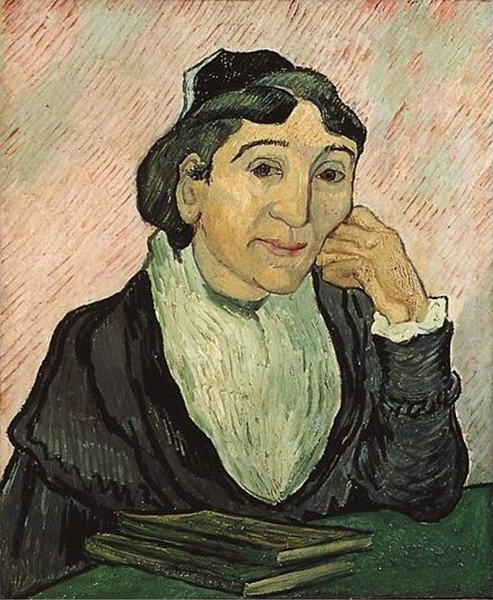

Van Gogh moved out of the Hotel Carrel and into a room in Cafe de la Gare very near the Yellow House. (The building is now entirely gone.) The owners of Cafe de la Gare were Joseph and Marie Ginoux. Joseph Ginoux is featured in The Night Cafe painting, which captures the bleakness of his own establishment. Madame Marie Ginoux sat for both Van Gogh and Gauguin, much later in the fall. When Van Gogh was hospitalized in Saint Remy, the following year, he would produce The Arlesienne, based on his earlier work. Evident in the depiction of Madame Ginoux in Gauguin's and Van Gogh's paintings is the divergence of the artists' styles.

In May 1888, while Van Gogh lived at Cafe de la Gare, he rented a room at the Yellow House to serve as his studio. By fall, he would be completely moved into the Yellow House, awaiting Gauguin's arrival.

Although Van Gogh had a high regard for Joseph Ginoux, he still had this to express to Theo about his lodgings at Cafe de La Gare.

I’d given a piece of my mind to the said lodging-house keeper who isn’t a bad man after all, and I’d told him that to get my own back on him for having paid him so much money for nothing, I’d paint his whole filthy old place as a way of getting my money back.

Walk further down Rue Voltaire until you see the Arles Roman Amphitheater.

You won't miss the Amphitheater

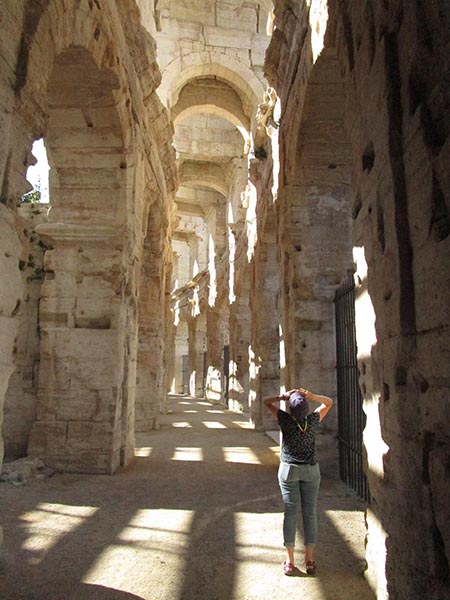

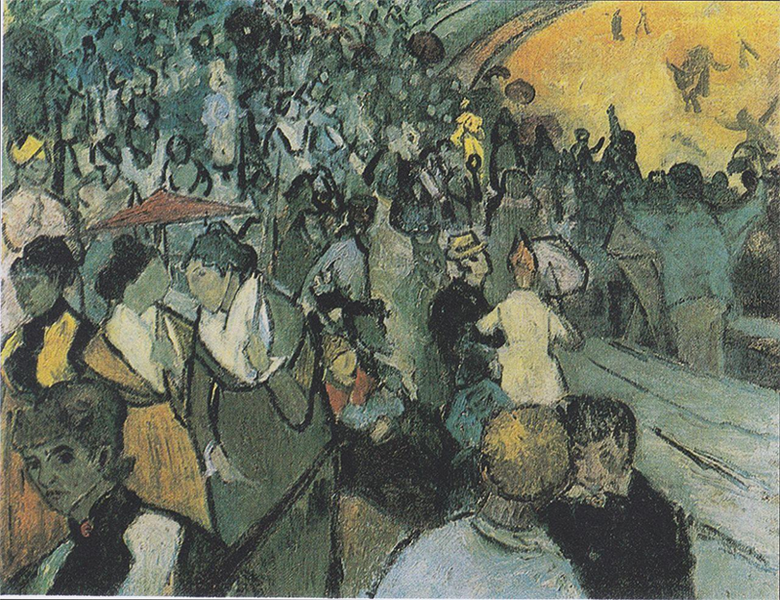

The Roman amphitheater is spectacular to see, even at dusk. The arena is still home to bullfighting events. The first event in the Arlesian bullfighting season takes place in early spring each year around Easter.

We know from his letters that Van Gogh occasionally saw a bull fight -- but he seemed more enthralled by the crowd than either the Roman Amphitheater or the bull fight itself. This seems evident in the painting titled 'The Arena in Arles' where the bullfight and the setting take backstage to the people in the stands.

By the way, I have seen bullfights in the arena, or rather sham fights, seeing that the bulls were numerous but there was nobody to fight them. However, the crowd was magnificent, those great colourful multitudes piled up one above the other on two or three galleries, with the effect of sun and shade and the shadow cast by the enormous ring.

You approached the amphitheater initially from the north. After you are done viewing the amphitheater walk around it to the south side following the Rond-Pointe de Arenes, which is the road that circles the amphitheater. If you walk around on the west side, the distance is shorter. Look for Rue Porte de Laure. Rue Porte de Laure is on the right side of the building pictured below. If you can imagine entering the amphitheater circle at 12 o'clock, you are exiting the circle at 7 o'clock. You will travel counter-clockwise.

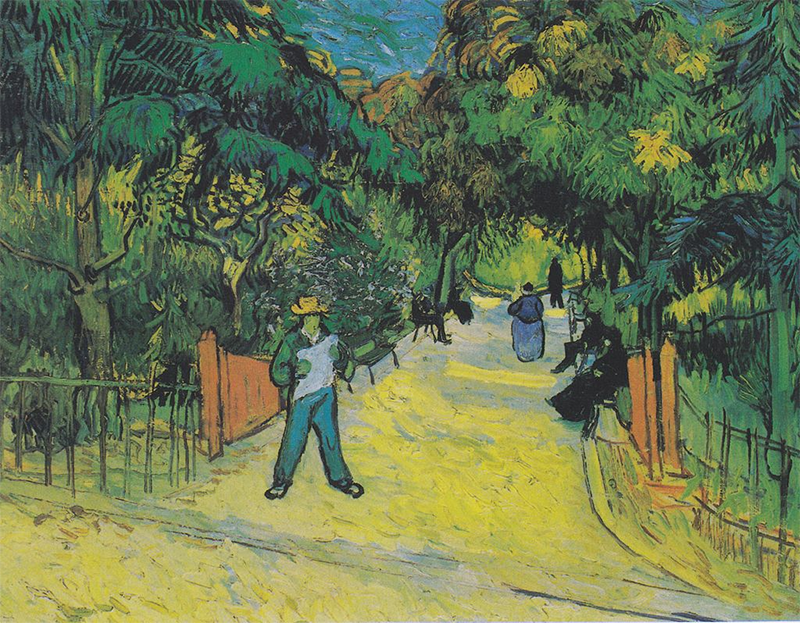

Follow Rue de Laure to the Jardin d’Eté (summer park). Look at our map once to learn where in the park you will find the panel pictured below and stand at the very vantage point Van Gogh used to paint 'Entrance of the Public Garden at Arles'.

You are looking for this:

Van Gogh painted in several gardens near his Yellow House. There was a small public garden across from his house. There was the garden just to the south of the Roman Theater that featured in his painting titled 'Entrance of the Public Garden at Arles' and there was the city hospital garden. In his paintings and sketches, Van Gogh captured both the common Arlesians and the natural beauty of the gardens.

But I will not say more about that, because it will be as clear as daylight to you when I begin to do things more seriously. At the moment I am working on another square size 30 canvas, another garden or rather a walk under plane trees, with the green turf, and black clumps of pines.

You did well to order the paints and the canvas, because the weather is magnificent. We still have the mistral, but there are calm intervals and then it is wonderful.

We're headed to L'espace Van Gogh. If you get lost, there are signs. There are also quicker ways to get there, but this is the most interesting route. It is about 1/3rd of a mile.

You can walk through the park, but eventually you will want to be on the main boulevard named Boulevard de Lices. It is that main, busy thoroughfare just to the south of the park. We won't stay on it for very long.

Walk to Rue Jean Juares. It is the first major north-south route just west of the park. Take a right and go north on Rue Jean Juares for about 300 feet to where Rue du Cloitre and Rue de la République meet at Place de la République where stands the broken obelisk of the Roman Emperor Constantine II. The broken obelisk was mended and stands at the center of the plaza. Remember this spot. We need to return to it after visiting L'Espace Van Gogh.

Continue west on Rue de la République to Rue de President Wilson. Turn left on Rue de President Wilson and continue south for about 200 feet until you come to Place Felix Rey. Turn right and look for the entrance to L'Espace Van Gogh, the hospital gardens (now the library gardens). You will learn more about Dr. Felix Rey in the next location.

To find the entrance to L'Espace Van Gogh, look for the following doorway. Also look for signs.

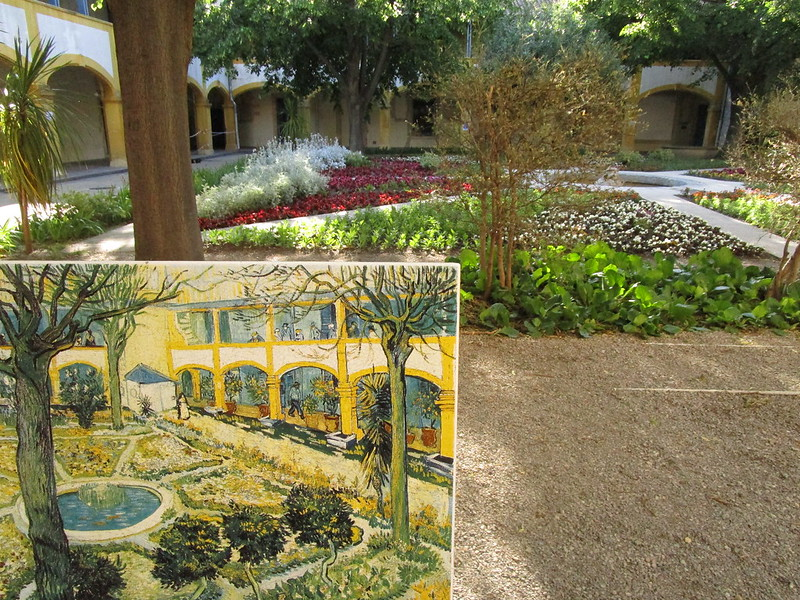

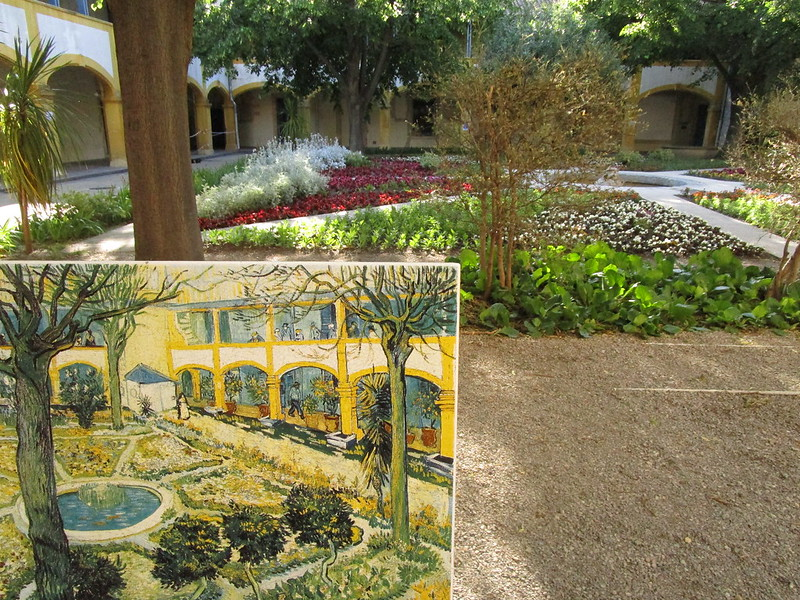

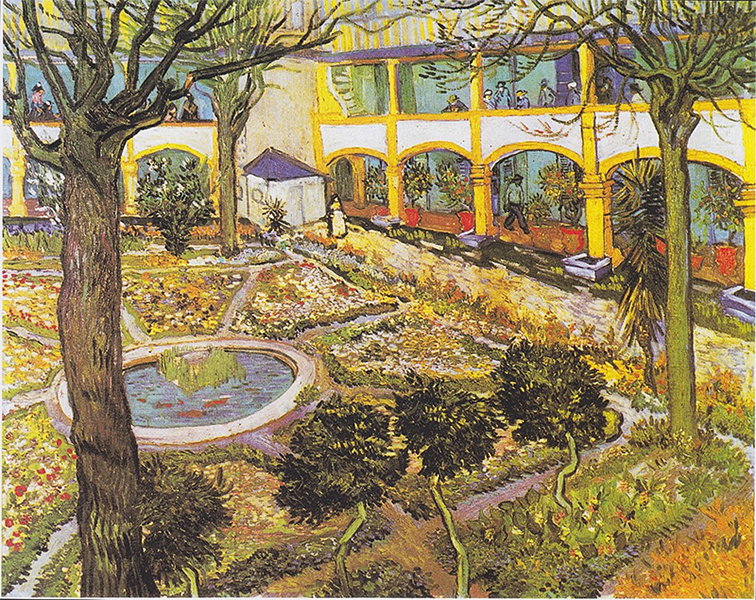

Once you are in the space of the hospital garden, look for the panel that displays Van Gogh's painting of the gardens.

You are looking for this:

L'espace Van Gogh is the garden of the hospital where Van Gogh stayed. The garden was re-designed to match the painting that made this space famous. Life imitates art.

Van Gogh's stay at the hospital that led to this painting and to all of the sketches and paintings done from the wards and arcade of the hospital was caused by a tragic event on the eve of Christmas, 1888.

To recap, Van Gogh had high hopes that the artist Paul Gaugin would help inaugurate an artistic school of the south. Gauguin joined Van Gogh in October 1888 and stayed with him in the Yellow House, mostly out of an obligation to Theo Van Gogh who was organizing small exhibitions of Gauguin's work. Some of Gauguin's work even sold. But by December, Vincent and he were quarreling. On Christmas Eve, Gauguin, feeling physically threatened, left the Yellow House for good. Van Gogh responded by slashing off the lobe of his ear and presenting it to a woman in a nearby brothel. All of these frustrations converged at that moment: the loss of his friend, the collapse of his dream for an artist community, the debt to his brother, his brother's impending marriage, Van Gogh's relationship frustrations, his illness.

Joseph Roulin, the postman, wrote the following to Theo about his own observations just days before the incident:

I have been to see your brother Vincent. I promised to tell you what I thought of him. I am sorry to tell you that I think he is lost. Not only is his mind affected, but also he is very weak and despondent.

Of his free will, Vincent sought admission to the local hospital and was cared for by Dr. Felix Rey who helped Van Gogh heal both physically and mentally. The letter from Dr. Rey to Theo describes Vincent's state of mind.

Gauguin returned to Paris and, by May, the people of Arles petitioned to have Van Gogh committed. But again, of his own free will, he moved to Saint Remy en Provence and was admitted to Saint-Paul Asylum.

As a side note, Saint Remy is less than twenty miles from Arles. Following a marked trail, you can walk up a hill from the center of town to Saint Paul de Mausole where Vincent van Gogh lived toward the end of his life. The pilgrimage is well worth the time. On the way to the hospital, you will pass the olive orchards that Van Gogh painted, and view the hospital grounds and Alpilles mountains as Van Gogh viewed and painted them. It is in Saint Remy, in June of 1889, where Van Gogh painted his, perhaps, most famous painting: "The Starry Night".

One last destination for the main part of the tour. It is the Place du Forum. Do you remember the obelisk? You need to retrace your steps back to the obelisk. (Back up President Wilson and turn right on Rue de la Republique.) After you return to the plaza of the obelisk, look for the road that runs up the eastern edge of the plaza headed north. That road is called Place de la République.

This road takes you alongside the Church of St. Trophime, the former cathedral of Arles and the site of an even older church that dates back to the 5th century. Van Gogh mentions it in his letter to Theo in March, 1888.

There’s a Gothic porch here that I’m beginning to think is admirable, the porch of St Trophime, but it’s so cruel, so monstrous, like a Chinese nightmare, that even this beautiful monument in so grand a style seems to me to belong to another world, to which I’m as glad not to belong as to the glorious world of Nero the Roman.

Must I tell the truth and add that the Zouaves, the brothels, the adorable little Arlésiennes going off to make their first communion, the priest in his surplice who looks like a dangerous rhinoceros, the absinthe drinkers, also seem to me like creatures from another world?

After you have viewed the church, continue along the road. It will take you to Rue de l'Hotel de Ville (city hall road). Go north on Rue de l'Hotel de Ville for about 100 feet to Plan de la Cour.

Turn left on Plan de la Cour. This is the first major left. Keep walking for about 175 feet and then turn right on Rue du Palais. Follow it for another 175 feet right into the Place du Forum. Look for Cafe Van Gogh. Your map will help find the right location in the Place du Forum.

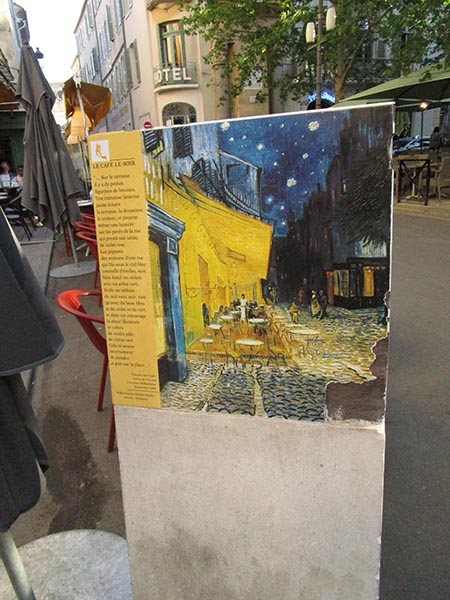

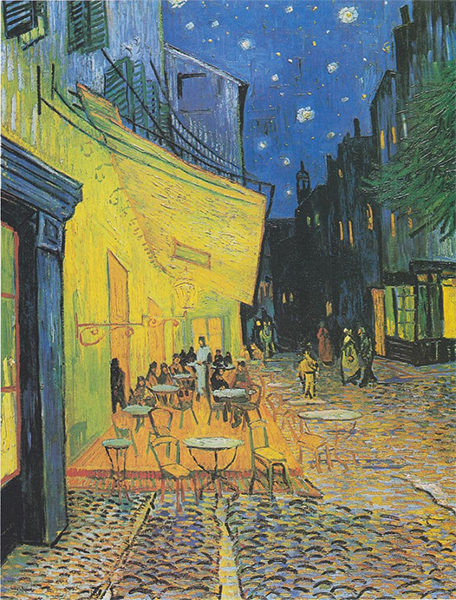

You are looking for this:

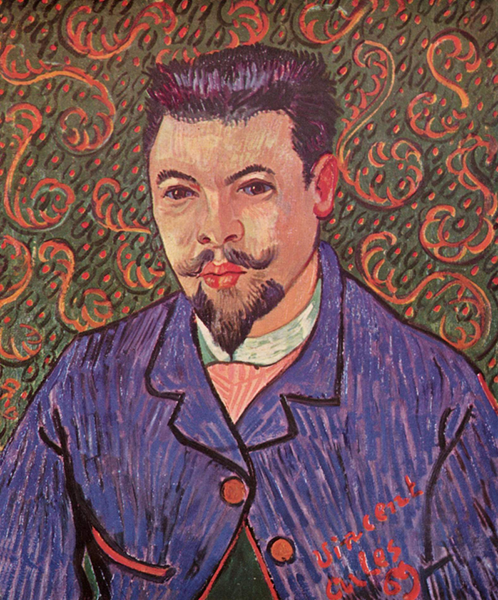

Le Café Van Gogh

We end the primary part of our tour here, in the Place du Forum. The Place du Forum is a rectangular plaza that was the center of the city during Roman Times. On the south end of the plaza stands the Grand Hotel Nord-Pinus, with the facade of an ancient Roman temple built into its wall. Some art scholars have indicated, in several paintings and drawings, even when Roman ruins were within view of Van Gogh, they were excluded from his paintings. Toward the southeast corner of the plaza stands Café Van Gogh. This is the original location of Café Terrace at Night. Café Van Gogh was restored in the early 90s to reflect the vibrancy of the painting. Van Gogh describes the painting of the scene in a letter to his sister. You can rest at any of the cafés in the Cafe Du Forum before opting to take in some of the additional sites offered by our walking tour.

It is already a few days since I started writing this letter, and now I will continue it. In point of fact I was interrupted these days by my toiling on a new picture representing the outside of a café at night. On the terrace there are the tiny figures of drinkers. An immense yellow lantern illuminates the terrace, the façade and the sidewalk, and even casts its light on the pavement of the streets, which takes a pinkish violet tone. The gables of the houses in the street stretching away under a blue sky spangled with stars are dark blue or violet with a green tree. Here you have a night picture without black in it, done with nothing but beautiful blue and violet and green, and lemon-yellow. It amuses me enormously to paint the night right on the spot. They used to draw and paint the picture in the daytime after the sketch. But I find satisfaction in painting the thing immediately.

Of course it's true that in the dark I may mistake a blue for a green, a blue-lilac for a pink-lilac, for you cannot distinguish the quality of a hue very well. But it is the only way to get rid of the conventional night scenes with their poor sallow whitish light, when even a simple candle gives us the richest yellows and orange tints.

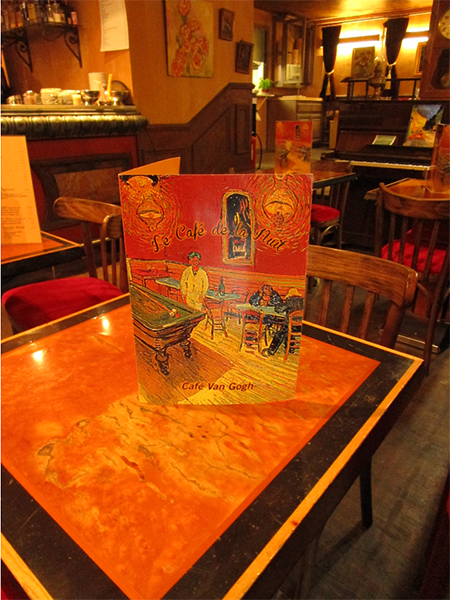

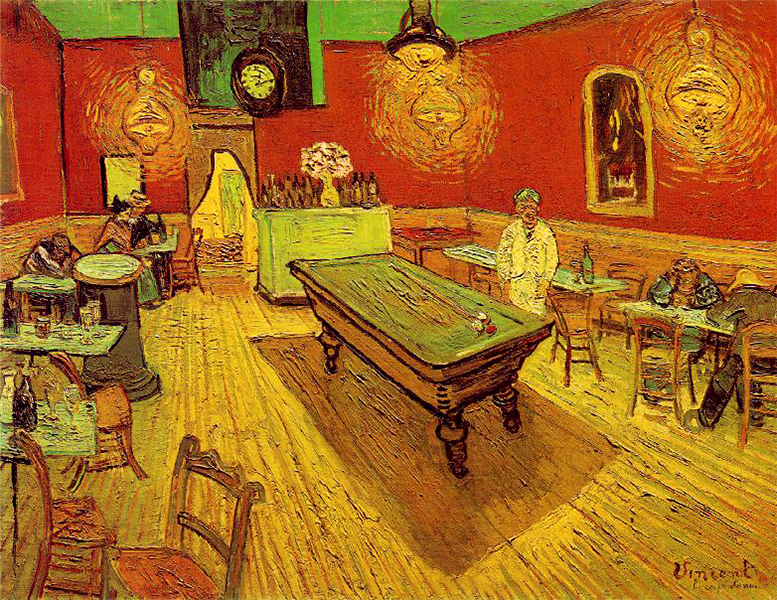

In his letter, Van Gogh also describes the painting of a cafe interior with a green billiard table. Night cafes stayed open all night to house men who were too drunk to be admitted into boarding rooms as well as others who were down-and-out. The scene is recreated in the upper floor of Cafe Van Gogh, although the original location was near the Yellow House.

The Night Café (Place Lamartine) Arles, September 1888

The room is blood red and dark yellow with a green billiard table in the middle; there are four lemon-yellow lamps with a glow of orange and green. Everywhere there is a clash and contrast of the most alien reds and greens, in the figures of little sleeping hooligans, in the empty dreary room, in violet and blue. The blood-red and the yellow-green of the billiard table, for instance, contrast with the soft tender Louis XV green of the counter, on which there is a rose nosegay. The white clothes of the landlord, watchful in a corner of that furnace, turn lemon-yellow, or pale luminous green.

If you opt to walk to Alyscamps (the necropolis) and then on to Pont Van Gogh (de Langlois draw bridge), you should plan on a 1/2 mile hike and then 1 1/2 miles. The drawbridge is quite a distance. We can't guide you there safely because you will be crossing a major highway and then a canal. You'll need to ask for directions.

The Alyscamps is a necropolis, a city of the dead or burial place, that dates back to Roman times. The Romans outlawed burials within the limits of the city. Towns that grew up under Roman management were typically characterized by roads outside the city perimeter that were lined with tombs, sarcophagi and memorials to the dead.

Van Gogh ventured out to the city limits and painted and sketched many scenes here.

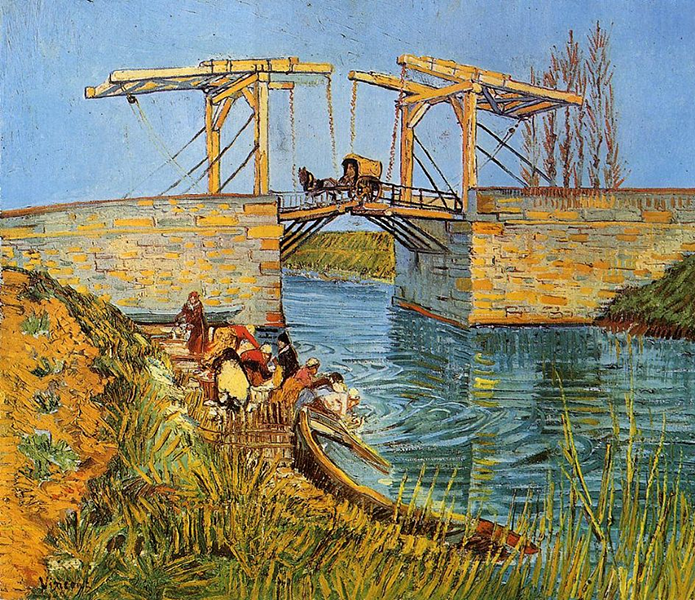

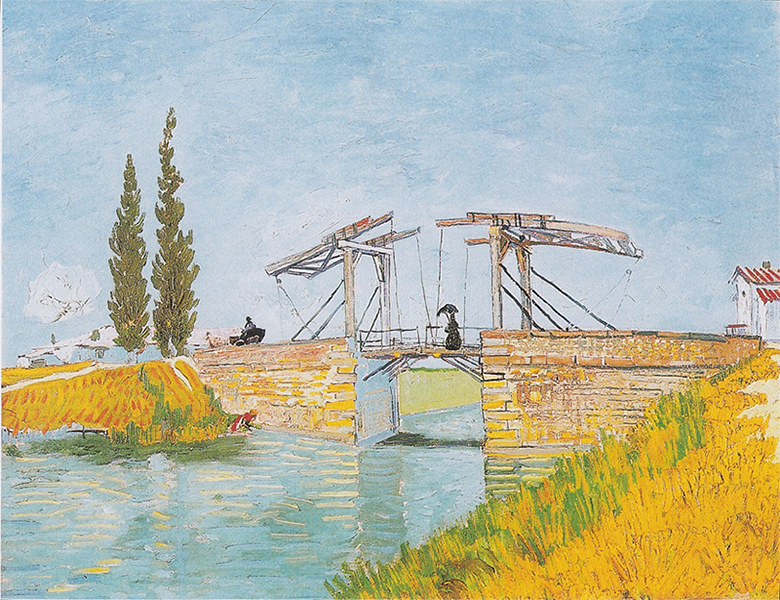

You've completed the pilgrimage. And, by venturing out to the Langlois Bridge, you are back in that hopeful time of March, 1888. Van Gogh had just recently arrived in Arles when he made studies of the Langlois drawbridge. He dedicated the first of these paintings to another painter. His brother, Theo Van Gogh, was currently exhibiting several of Vincent's paintings in the Salon des Independants. It was a new and hopeful time for Vincent.

As for my work, I brought back a size 15 canvas today. It is a drawbridge over which passes a little cart, standing out against a blue sky - the river blue as well, the banks orange coloured with grass and a group of women washing linen in smocks and multicoloured caps. And another landscape with a little rustic bridge and washerwomen also.

February 21, 1888

My dear Theo,

During the journey I thought of you at least as much as I did of the new country that I was seeing.

Only I told myself that maybe later on you will often come here yourself. It seems to me almost impossible to be able to work in Paris unless one has a refuge where one can recuperate and regain one's tranquillity and poise. Without that, one would get hopelessly exhausted.

Now I'll begin by telling you that there's at least 60 centimeters of fallen snow everywhere, and it is still falling.

Arles doesn't seem any bigger than Breda or Mons.

Before arriving at Tarascon I noticed a magnificent landscape of immense yellow rocks, strangely intricate with the most imposing shapes.

In the tiny valleys between these rocks were rows of small round trees with foliage of olive-green or grey-green, which could well be lemon trees.

But here in Arles the country appears flat. I saw some magnificant red terrain planted with grapevines, with a background of mountains of the most delicate lilac. And the landscapes in the snow, with the summits white against a sky as luminous as the snow, were just like winter landscapes done by the Japanese.

Here is my address:

Restaurant Carrel,

30 Rue Cavalerie,

(Departement Bouches du Rhône) Arles.

I have only taken a little trip into the town so far, since I was more or less dog-tired last night.

I'll write soon. In an antique shop on the same street that I went into yesterday, the man told me he knew of a Monticelli.

With a good handshake to you and our comrades.

Ever yours, Vincent

March 14, 1888

My dear Theo,

I thank you very much for your letter, which I had not dared to expect so soon, as far as the 50-fr. note which you added was concerned.

I see that you have not yet had an answer from Tersteeg. I don't think that we need press him with a new letter. However, if you have any official business to transact with B. V. & Co. in The Hague, you might mention in a P. S. that you are rather surprised that he has in no way acknowledged the receipt of the letter in question.

As for my work, I brought back a size 15 canvas today. It is a drawbridge over which passes a little cart, standing out against a blue sky - the river blue as well, the banks orange coloured with grass and a group of women washing linen in smocks and multicoloured caps. And another landscape with a little rustic bridge and washerwomen also.

Finally an avenue of plane trees close to the station. Altogether 12 studies since I've been here.

The weather here is changeable, often windy with turbulent skies, but the almond trees are beginning to flower everywhere. I am very happy that the paintings are going to the Independents. You are right to go to see Signac at his house. I was very glad to read in today's letter that he made a more favourable impression on you than the first time. In any case I am glad to know that after today you will not be alone in the apartment.

Remember me kindly to Koning. Are you well? I am better myself, except that eating is a real ordeal, since I have a touch of fever and no appetite, but it's only a question of time and patience.

I have company in the evening, for the young Danish painter who is here is a decent soul: his work is dry, correct and timid, but I do not object to that when the painter is young and intelligent. He originally began studying medicine: he knows Zola, de Goncourt, Guy de Maupassant, and he has enough money to do himself well. And with all this, a very genuine desire to do very different work than what he is producing now.

I think he would be wise to delay his return home for a year, or to come back here after a short visit to his friends.

But, my dear brother, you know that I feel as though I am in Japan - I say no more than that, and I still haven't seen anything in its usual splendour yet.

That's why (even though I'm vexed that just now expenses are heavy and the paintings worthless), that's why I don't despair of the future success of this idea of a long sojourn in the Midi.

Here I am seeing new things, I am learning, and if I take it easy, my body doesn't refuse to function.

For many reasons I should like to establish some sort of little retreat, where the poor cab horses of Paris - that is yourself and several of our friends, the poor impressionists - could go out to pasture when they get too exhausted.

I was present at the Inquiry into a crime committed at the door of a brothel here; two Italians killed two Zouaves. I took advantage of the opportunity to go into one of the brothels in a little street called “des ricolettes.”

That is the extent of my amorous adventures among the Arlésiennes. The mob all but (the Southerner, like Tartarin, being more energetic in good intentions than in action) - the mob, I repeat, all but lynched the murderers locked up in the town hall, but in retaliation all the Italians - men and women, the Savoyard monkeys included - have been forced to leave town.

I should not have told you about this, except that it means I've seen the streets of this town full of excited crowds. And it was indeed a fine sight.

I made my last three studies with the perspective frame which you know I use. I attach some importance to the use of the frame because it seems not unlikely to me that in the near future many artists will make use of it, just as the old German and Italian painters certainly did, and, as I am inclined to think, the Flemish too. The modern use of it may differ from the ancient practice, but in the same way isn't it true that in the process of painting in oils one gets very different effects today from those of the men who invented the process, Jan and Hubert van Eyck? And the moral of this is that it's my constant hope that I am not working for myself alone. I believe in the absolute necessity of a new art of colour, of design, and - of the artistic life. And if we work in that faith, it seems to me that there is a chance that we do not hope in vain.

You must know that I am actually ready to send some studies off to you, only it is impossible to roll them up yet. A hearty handshake. On Sunday I shall write to Bernard and de Lautrec, because I solemnly promised to, and shall send you those letters as well. I am deeply sorry for Gauguin's plight, especially because his health is shaken: he no longer has the kind of temperament that profits from hardships - on the contrary, this will only exhaust him from here on, and that will spoil him for his work. Goodbye for the present.

Ever yours, Vincent

April, 1888

My dear comrade Bernard,

Thanks for your kind letter and for the enclosed sketches of your decoration, which I think very funny. Sometimes I regret that I cannot make up my mind to work more at home and extempore. The imagination is certainly a faculty which we must develop, one which alone can lead us to the creation of a more exalting and consoling nature than the single brief glance at reality - which in our sight is ever changing, passing like a flash of lightning - can let us perceive.

A starry sky, for example. See, that's a thing I'd like to try to do, just as by day I want to try to paint a green meadow spangled with starry dandelions. Yet how can I do it, unless I work it out at home, and from my imagination? Of course, this faults my idea while yours gets praised.

At the moment I am absorbed in the blooming fruit trees, pink peach trees, yellow-white pear trees. My brush stroke has no system at all. I hit the canvas with irregular touches of the brush, which I leave as they are. Patches of thickly laid-on colour, spots of canvas left uncovered, here or there portions that are left absolutely unfinished, repetitions, savageries; in short, I am inclined to think that the result is so disquieting and irritating as to be a godsend to those people who have preconceived ideas about technique. For that matter here is a sketch, the entrance to a Provençal orchard with its yellow fences, its enclosure of black cypresses (against the mistral), its characteristic vegetables of varying greens: yellow lettuces, onions, garlic, emerald leeks.

Working directly on the spot all the time, I try to grasp what is essential in the drawing - later I fill in the spaces which are bounded by contours - either expressed or not, but in any case felt - with tones which are also simplified, by which I mean that all that is going to be soil will share the same violet-like tone, that the whole sky will have a blue tint, that the green vegetation will be either green-blue or yellow-green, purposely exaggerating the yellows and blues in this case.

In short, my dear comrade, in no case an eye-deceiving job. 1

As for visiting Aix, Marseilles, Tangier, no fear of that. If notwithstanding this I should go there, it would be in search of cheaper lodgings. Otherwise I am convinced that even if I were to work all my life, I should not be able to do one half of all that is characteristic in this town alone.

By the way, I have seen bullfights in the arena, or rather sham fights, seeing that the bulls were numerous but there was nobody to fight them. However, the crowd was magnificent, those great colourful multitudes piled up one above the other on two or three galleries, with the effect of sun and shade and the shadow cast by the enormous ring.

I wish you a good journey - a handshake in thought.

Your friend, Vincent

June 28, 1888

My dear Theo,

I suppose it was to convince me that, being myself one of the most absent-minded of mortals, I have no right whatever to reproach these Southerners with their carelessness. I was idiot enough once more to address my letter 54 Rue de Laval, instead of 54 Rue Lepic, so the post-office clerks, who sent me back the letter opened, have had the pleasure of edifying themselves by the contemplation of Bernard's brothel. I hasten to send on the letter as it is.

This morning I received part of the order for paints from Tanguy.

His cobalt is too bad for us to order any more of it from him. As his chromes are rather good, we can go on ordering those. But instead of carmine he sent some dark madder, which isn't too important, but not to have any more carmine at all would mean a very serious shortage in his poor old show. It is not his fault, but in the future I will put “Tanguy” beside the names of the paints that one can buy from him.

Yesterday and today I worked on the sower, which I have completely worked over. The sky is yellow and green, the ground violet and orange. There is certainly a picture of this kind to be painted of this splendid subject, and I hope it will be done someday, either by me or by someone else.

This is the point. The “Christ in the Boat” by Eugène Delacroix and Millet's “The Sower” are absolutely different in execution. The “Christ in the Boat” - I am speaking of the sketch in blue and green with touches of violet, red and a little citron-yellow for the nimbus, the halo - speaks a symbolic language through colour alone.

Millet's “Sower” is a colourless grey, like Israëls's pictures.

Now, could you paint the Sower in colour, with a simultaneous contrast of, for instance, yellow and violet (like the Apollo ceiling of Delacroix's which is just that, yellow and violet), yes or no? Why, yes. Well, do it then. Yes, that is what old Martin said, “The masterpiece is up to you.” But try it, and you tumble into a regular metaphysical philosophy of colour à la Monticelli, a mess that is damnably difficult to get out of with honour.

And it makes you as absent-minded as a sleepwalker. And yet if only one could do something good.

Well, let's be of good heart, and not despair. I hope to send you this attempt along with some others soon. I have a view of the Rhône - the iron bridge at Trinquetaille - in which the sky and the river are the colour of absinthe; the quays, a shade of lilac; the figures leaning on their elbows on the parapet, blackish; the iron bridge, an intense blue, with a note of vivid orange in the blue background, and a note of intense malachite green. Another very crude effort, and yet I am trying to get at something utterly heartbroken and therefore utterly heartbreaking.

Nothing from Gauguin. I certainly hope to get your letter tomorrow. Forgive my carelessness. A handshake.

Ever yours, Vincent

Many thanks for the paints. Goodbye for now.

Return to Trinquetaille Bridge

September 17, 1888

My dear Theo,

Many thanks for your letter and the 50-franc note which it contained.

I also received Maurin's drawing, which is magnificent. That man is a great artist. Last night I slept in the house, and though there are some things still to be done, I feel very happy in it. Besides, I feel that I can make something lasting out of it, from which others can profit as well. Now money spent will not be money lost, and I think that you will soon see the difference. At present it reminds me of Bosboom's interiors, with the red tiles, the white walls, the furniture of white deal and walnut and the glimpses of an intense blue sky and greenery through the windows. Its surroundings, the public garden, the night cafés and the grocer's, are not Millet, but instead they are Daumier, absolute Zola.

And that is quite enough to supply one with ideas, isn't it?

Yesterday I had already written to you, saying that if I figure the two beds at 300 francs, the price will not allow of any further reduction. If I have already bought more than that anyway, it is because I put half of last week's money into it. Yesterday again I had to pay 10 francs to the innkeeper and 30 francs for a mattress.

At the moment I have 5 francs left, so I must beg you to send me what you can, or else - but do let it be by return mail - a louis to last me the week, or indeed 50 francs if it's possible.

In one way or another I'd like to be able to count on getting this month, meaning the whole month, another 100 instead of the 50, as I asked you in yesterday's letter.

If I myself save 50 francs during the month, and add the other 50 to that, I should have spent altogether 400 francs on furniture. My dear Theo, here we are on the right road at last. Certainly it does not matter being without hearth or home and living in cafés like a traveler so long as one is young, but it was becoming unbearable to me, and more than that, it did not fit in with thoughtful work. So my plan is all complete, I will try to paint up to the value of what you send me every month, and after that I want to paint to pay for the house. What I paint for the house will be to repay you for previous expenditure.

I am still a bit commercial, in the sense that I long to prove that I pay my debts, and that I know how much I want for the goods which this blasted poor painter's profession keeps me working at.

Altogether I think I can be almost sure of bringing off a set of decorations which will be worth 10.000 francs in time.

Listen to me. If we set up a studio and refuge here for some comrade who is hard up, no one will ever be able to reproach either you or me with living and spending for ourselves alone. Now to establish such a studio requires a floating capital, and I have eaten that up during my unproductive years, but now that I am beginning to produce something, I shall pay it back.

I assure you that I think it is essential for you as well as me, and no more than our right, too, to always have a louis or two in our pockets, and some stock of goods to do business with. But my idea is that in the end we shall have founded and left to posterity a studio where one's successor could live. I do not know if I explain myself clearly enough, but in other words we are working for an art and for a business method that will not only last our lifetime, but can still be carried on by others after us.

For your part you do this in your business, and it is certain that you will make good in the end, even though you have plenty to harry you at the moment. But for my part I foresee that other artists will want to see colour under a stronger sun, and in a more Japanese clarity of light.

Now if I set up a studio and refuge right at the gates of the South, it's not such a crazy scheme. And it means that we can work on serenely. And if other people say that it is too far from Paris, etc., let them, so much the worse for them. Why did the greatest colourist of all, Eugene Delacroix, think it essential to go south and right to Africa? Obviously, because not only in Africa but from Arles onward you are bound to find beautiful contrasts of red and green, of blue and orange, of sulphur and lilac.

And all true colourists must come to this, must admit that there is another kind of colour than that of the North. I am sure if Gauguin came, he would love this country; if he doesn't it's because he has already experienced more brightly coloured countries and he will always be a friend, and one with us in principle.

And someone else will come in his place.

If what one is doing looks out upon the infinite, and if one sees that one's work has its raison d'être and continuance in the future, then one works with more serenity.

Now you have a double right to that.

You are kind to painters, and I tell you, the more I think it over, the more I feel that there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people. You will say that then it would be a good thing to do without art and artists. That is true in the first instance, but then the Greeks and the French and the old Dutchmen accepted art, and we see how art always comes to life again after inevitable periods of decadence, and I do not think that anyone is the better for abhorring artists and their art. At present I do not think my pictures worthy of the advantages I have received from you. But once they are worthy, I swear that you will have created them as much as I, and that we are making them together.

But I will not say more about that, because it will be as clear as daylight to you when I begin to do things more seriously. At the moment I am working on another square size 30 canvas, another garden or rather a walk under plane trees, with the green turf, and black clumps of pines.

You did well to order the paints and the canvas, because the weather is magnificent. We still have the mistral, but there are calm intervals and then it is wonderful.

If there were less mistral, this place would really be as lovely as Japan, and would lend itself as well to art.

As I was writing, a very kind letter arrived from Bernard; he is thinking of coming to Arles this winter, just a whim, but it is possible that Gauguin is sending him as a substitute, and would rather stay in the North himself. We shall soon know, because I am convinced that he will write you one way or the other.

In his letter Bernard speaks of Gauguin with great respect and sympathy, and I am sure that they understand one another.

And I really think that Gauguin has done Bernard good.

Whether Gauguin comes or not, he will remain friends with us, and if he does not come now, he will come another time.

I feel instinctively that Gauguin is a schemer who, seeing himself at the bottom of the social ladder, wants to regain a position by means which will certainly be honest, but at the same time, very politic.

Gauguin little knows that I am able to take all this into account. And perhaps he does not know that it is absolutely necessary for him to gain time, and that with us he will gain that, if he gains nothing else.

If someday he decamps from Pont-Aven with Laval or Maurin without paying his debts, I think in his case he would still be justified, exactly like any other creature at bay. I do not think it would be wise to offer Bernard straight off 150 francs for a picture every month, as you did Gauguin. And Bernard, who has evidently been over and over the whole business with Gauguin - isn't he rather counting on taking Gauguin's place?

I think it will be necessary to be very firm and very explicit about the whole thing.

And without giving any reasons, to speak very plainly.

I cannot blame Gauguin - speculator though he may be as soon as he wants to risk something in business, only I will have nothing to do with it. I would a thousand times rather go on with you, whether you are with the Goupils or not.

And in my opinion, you know, the new dealers are exactly and in every way the same as the old.

In principle, and in theory, I am for an association of artists who guarantee each other's work and living, but in principle and in theory I am equally against attempts to destroy old, established businesses. Let them rot in peace, and die a natural death. It is pure presumption to hope to regenerate trade. Have nothing to do with it; let's guarantee a living among ourselves, live like a family, like brothers and friends, and this even if it should not succeed - I would like to be in this, but I will never have anything to do with an attack on other dealers.

With a handshake, and I hope that what I have been obliged to ask you will not be too terribly inconvenient. But I did not want to postpone sleeping at home. And in case you are short yourself, 20 francs more will get me through the week, but it is urgent.

Ever yours, Vincent

September, 1888

My dear Theo,

Thank you a thousand times for your kind letter and the 300 francs it contained; after some worrying weeks I have just had a much better one. And just as worries do not come singly, neither do the joys. For just because I am always bowed down under this difficulty of paying my landlord, I made up my mind to take it gaily. I swore at the said landlord, who after all isn't a bad fellow, and told him that to revenge myself for paying him so much money for nothing, I would paint the whole of his rotten shanty so as to repay myself. Then to the great joy of the landlord, of the postman whom I had already painted, of the visiting night prowlers, and of myself, for three nights running I sat up to paint and went to bed during the day. I often think that the night is more alive and more richly coloured than the day.

Now, as for getting back the money I have paid to the landlord by my painting, I do not dwell on that, for the picture is one of the ugliest I have done. It is the equivalent, though different, of the “ Potato Eaters.”

I have tried to express the terrible passions of humanity by means of red and green.

The room is blood red and dark yellow with a green billiard table in the middle; there are four lemon-yellow lamps with a glow of orange and green. Everywhere there is a clash and contrast of the most alien reds and greens, in the figures of little sleeping hooligans, in the empty dreary room, in violet and blue. The blood-red and the yellow-green of the billiard table, for instance, contrast with the soft tender Louis XV green of the counter, on which there is a rose nosegay. The white clothes of the landlord, watchful in a corner of that furnace, turn lemon-yellow, or pale luminous green.

I am making a drawing of it with the tones in watercolour to send to you tomorrow, to give you some idea of it.

I wrote this week to Gauguin and Bernard, but I did not talk about anything but pictures, just so as not to quarrel when there is probably nothing to quarrel about.

But whether Gauguin comes or not, if I were to get some furniture, henceforth I should have, whether in a good spot or a bad one is another matter, a pied à terre, a home of my own, which frees the mind from the dismalness of finding oneself in the streets. That is nothing when you are an adventurer of twenty, but it is bad when you have turned thirty-five.

Today in the Intransigeant I noticed the suicide of M. Bing Levy. It can't be the Levy, Bing's manager, can it? I think it must be someone else.

I am greatly pleased that Pissarro thought something of the “Young Girl.” Did Pissarro say anything about the “Sower”? Afterwards, when I have gone further in these experiments, the “Sower” will still be the first attempt in that style. The “Night Café” carries on from the “Sower,” and so also do the head of the old peasant and of the poet, if I manage to do this latter picture.

It is colour not locally true from the point of view of the trompe d'oeil realist, but colour to suggest some emotion of an ardent temperament.

When Paul Mantz saw at the exhibition the violent and inspired sketch by Delacroix that we saw at the Champs Elysées - the “Bark of Christ” - he turned away from it, exclaiming in his article: “I did not know that one could be so terrible with a little blue and green.”

Hokusai wrings the same cry from you, but he does it by his line, his drawing; as you say in your letter - “the waves are claws and the ship is caught in them, you feel it.”

Well, if you make the colour exact or the drawing exact, it won't give you sensations like that.

Anyhow, very soon, tomorrow or next day, I will write to you again about this and answer your letter, and send you the sketch of the “Night Café.”

Tasset's parcel has arrived. I will write tomorrow on this question of the coarse grained colour. Milliet is coming to see you and pay his respects to you one of these days, he writes to me that he is coming back.

Thank you again for the money you sent. If I went first to look for another place, would it not very likely mean fresh expense, equal at least to the expense of a removal? And then should I find anything better all at once? I am so very glad to be able to do the furnishing, and it can't but help me on. Many thanks then, and a good handshake, till tomorrow.

Yours, Vincent.

September 28, 1888

My dear Theo, thank you very much of your letter and the 50 francs note that it contained. It is not good that the pains in the leg have come back - my god - it would be good it if it was possible if you could live in the Midi too, because I always think that we need each other, and the sun and good weather and the blue air are the strongest remedy. The weather here remains beautiful, and if it is always like this then it would be better than the paradise of those painters who are in Japan itself. I think about you and Gauguin and about Bernard all the time and everywhere. It is so beautiful and I would so like to see everybody here.

Included a small sketch of a 30 square canvas - in short the starry sky painted by night, actually under a gas jet. The sky is aquamarine, the water is royal blue, the ground is mauve. The town is blue and purple. The gas is yellow and the reflections are russet gold descending down to green-bronze. On the aquamarine field of the sky the Great Bear is a sparkling green and pink, whose discreet paleness contrasts with the brutal gold of the gas. Two colourful figurines of lovers in the foreground.

Also a sketch of a 30 square canvas representing the house and its setting under a sulphur sun under a pure cobalt sky. The theme is a hard one! But that is exactly why I want to conquer it. Because it is fantastic, these yellow houses in the sun and also the incomparable freshness of the blue. All the ground is yellow too. I will soon send you a better drawing of it than this sketch out of my head.

The house on the left is pink with green shutters. It's the one that is shaded by a tree. This is the restaurant where I go to dine every day. My friend the factor is at the end of the street on the left, between the two bridges of the railroad. The night café that I painted is not in the picture, it is on the left of the restaurant.

Milliet finds this horrible, but I don't need to tell you that when he says he doesn't understand that one can have fun doing a common grocer's shop and the stiff and proper houses without any grace, but I remember that Zola did a certain boulevard in the beginning of L'assommoir, and Flaubert a corner of the embankment of the Villette in the dog days in the beginning of Bouvard and Pécuchet which are not to be sneezed at.

It does me good to do difficult things. It does not prevent me from having a terrible need of, shall I say the word - of religion - then I go outside in the night to paint the stars and I dream ever of a picture like this with a group of lively figures of our pals.

Now I have had a letter from Gauguin who seems very sad, and says that certainly if he made a sale he will come, but he doesn't say clearly that if he would simply have his journey paid he would agree to come down here.

He says that the people where he lodges are, and have been, great to him, and that to leave them like that would be a bad thing to do. But that I turn a dagger in his heart if I would believe that he would not immediately come if he was able to. That besides, if you could sell his canvases at a low price he would be happy. I will send you his letter with the replies.

Certainly his arrival would be an increase of 100 percent in the importance of this enterprise of doing painting in the Midi. And once here, I don't see him leaving again because I believe that he would take root here. And I always tell myself that what you are doing in private would in the end, with his collaboration, be a more serious thing than just my work, without an increase in the expenses and you would have more satisfaction. Later on, if maybe one day you are on your own with the impressionist paintings you will only have to continue and to enlarge on those which actually exists. Finally Gauguin says that Laval found someone who will give him 150 francs per month for at least one year, and that Laval also would maybe come in February. And I have written to Bernard that I think that in the Midi he could not live for less than 3.50 or 4 francs per day just for lodging & food. He says that he believes that for 200 francs per month he would have food and lodging for all 3 which is not impossible, if we live & eat in the studio.

The Benedictine father must have been very interesting. What would, according to him, be the future religion? Probably he would always say the same as the past.

Victor Hugo says God is an eclipsing lighthouse, and certainly now we are passing through that eclipse.

I only wish that someone could prove to us something calming which comforted us, so that we stopped feeling guilty or unhappy and that we could go forward without losing ourselves in the solitude or nothingness, and without having to fear every step, or to nervously calculate the harm we may unintentionally be doing to others.

In odd Giotto's biography it said that he was always suffering and always full of ardour and ideas.

There, I would like to arrive at this assurance that makes one happy, cheerful and alive all the time. That would be easier to do in the country or a small town than in that Parisian furnace.

I would not be surprised if you will like the starry night and the ploughed fields - they are more tranquil than the other canvases. If the work always turned out like that I would have less concerns about money, because people would take to them more easily if the technique continued to be more harmonious. But this blasted mistral is very bothersome to do brushstrokes that hold and are well interwoven, with a feeling like music played with emotion.

With this calm weather I let myself go and I don't have to struggle against impossibilities

Tanguy's consignment arrived and I thank you very, very much for it because I also hope to be able to make something during autumn for the next exhibition. What is now the most pressing is 5 or even 10 meters of canvas. I write again that I will send Gauguin's letter with the reply.

Very interesting what you say of Maurin; at 40 francs his drawings are certainly not expensive. More and more I come to believe that the true and proper trade of painting is one has to let oneself go with one's taste, one's learning before the masters, in short one's faith. It is not any easier, I am convinced, to make a good painting that to find a diamond or a pearl; it requires pain and one must risk his life as a dealer or as an artist. But once one has some good stones then self doubt is not necessary, and one must boldly stick to a certain price. In the meantime… but while this idea encourages me to work, still naturally I suffer at having to spend money. But in the midst of my suffering this idea of the pearl came to me, and I would not be surprised if it didn't do you good too in times of discouragement. There are as few good paintings as there are diamonds.

And there is absolutely nothing dishonest about doing business with good stones. One can believe in oneself when one sees that the thing one is selling is good.Now, if people like paste, and it pleases them and since they ask for it, good, one can have it in the store, but it isn't enough to make one feel good about oneself with the good paintings, yet one can feel oneself and be firm, since it is a pure error that there is as much as one wants. Perhaps I am expressing myself badly, but I have thought about this a good deal these days, and calm has come to me about this Gauguin affair.

All these Gauguins are good stones, and so let us boldly be merchants of Gauguin.

Milliet says a good hello. I now have his portrait with a red kepi on emerald background, and in the background the arms of his regiment, the crescent and a 5-pointed star.

A good handshake and until next time and many thanks and I hope that the pains will not last long. Have you seen a doctor again[?] Look after yourself, because physical pain is so agonising.

Ever yours,

Vincent

Return to Starry Night on the Rhone

October 24, 1888

My dear Theo,

Thanks for your letter and the 50-fr. note. As you learned from my wire, Gauguin has arrived in good health. He gives me the impression he is even better than me.

Naturally he is very pleased with the sale you have effected, and I no less, since in this way certain expenses absolutely necessary for the installation need not wait, and will not weigh wholly on your shoulders. G. will certainly write you today. He is very, very interesting as a man, and I have every confidence that we shall do loads of things with him. He will probably produce a great deal here, and I hope perhaps I shall too.

And then I dare hope that the burden will be a little less heavy for you, and I even hope, much less heavy.

I myself realize the necessity to produce even to the extent of being morally crushed and physically drained by it, just because after all I have no other means of ever getting back what we have spent.

I cannot help it that my pictures do not sell.

The day will come when people will see that they are worth more than the price of the paint and my own living, very meager after all, that is put into them.

I have no other desire nor any other interest as to money or finance, than primarily to have no debts.

But my dear boy, my debt is so great that when I have paid it, when all the same I hope to succeed in doing, the pains of producing pictures will have taken my whole life from me, and it will seem to me then that I have not lived. The only thing is that perhaps the production of the pictures will become a little more difficult for me, and as to numbers, there will not always be so many.

It is agonizing to me that there is no demand for them now, because you suffer for it, but as far as I am concerned - if only you were not too worried by my bringing nothing in - it would pretty much be all the same to me.

But in money matters it is enough for me to realize this truth - that a man who lives for 50 years and spends 2000 a year has spent 100,000 francs, and must bring in 100,000 francs again. To do 1000 pictures at 100 francs during one's life as an artist comes very, very, very hard, but even when the picture is at 100 francs . . . once again . . . at times our task is very heavy. But there is no changing that.

We shall probably bypass Tasset altogether, because to a large extent we are going to use cheaper colours, Gauguin as well as I. And in the same way we are going to prepare the canvas ourselves. For a while I had a feeling that I was going to be ill, but Gauguin's arrival has so taken my mind off it that I'm sure it will pass. I must not neglect my food for a time, and that is all, absolutely all there is to it.

And after a time you will have some work again.

Gauguin brought a magnificent canvas, which he has exchanged with Bernard, Breton women in a green field, white, black, green, and a note of red, and the dull flesh tints. After all, we must all be of good cheer.

I believe that the time will come when I too shall sell, but I am so far behind with you, and while I go on spending, I bring nothing in. Sometimes the thought of it saddens me.

I am very glad of what you write, that one of the Dutchmen is coming to stay with you, so that you will not be alone any more, and it's all right, absolutely all right, especially since the winter will soon be here.

And now I am in a hurry and must go out and set to work again on another size 30 canvas.

Very soon, when Gauguin writes, I'll add another letter to his. Naturally, I don't know beforehand what Gauguin will say of this country, and of our life, but in any case he is very pleased with the good sale you have managed for him.

Goodbye for now, and a good handshake.

Ever yours,

Vincent

September 9 and September 16, 1888

My dear sister,

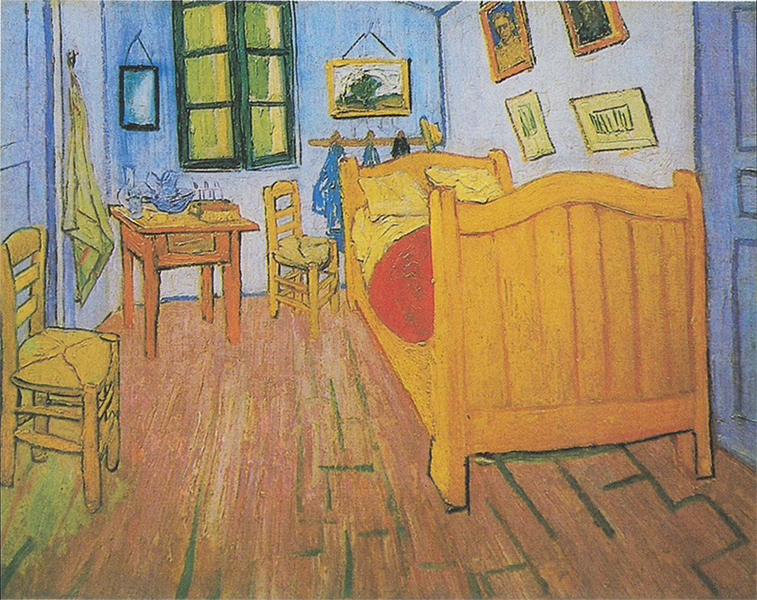

Your letter gave me a great deal of pleasure, and today I have the leisure to calmly reply. So your visit to Paris was quite a success. I should very much like you to come here next year too. At the moment I am furnishing the studio in order to always be ready to put somebody up. Because there are 2 little rooms upstairs looking onto a very pretty public garden, and from which one can see the sun rise in the morning. I will arrange one of these rooms to accomodate a friend, and the other will be for me.

In it I want nothing but straw-bottomed chairs and a table and a whitewood bed. The walls whitewashed, the tiles red. But I want a great wealth of portraits and painted studies of figures in it, which I intend to do in the course of time. I already have one to begin with, the portrait of a young Belgian impressionist. I have painted him a little like a poet, the head fine & nervous standing out against a background of a deep ultramarine night sky with the twinkling of stars.

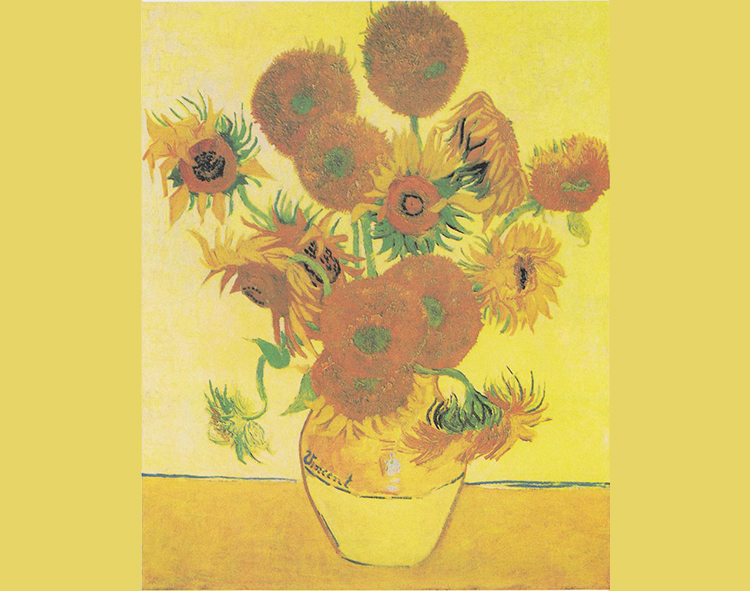

However, I want to have the other room just as elegant with a walnut bedstead and a blue coverlet. And all the rest, the dressing table as well as the cupboard, in dull walnut. In this very tiny room I want to put, in the Japanese manner, at least 6 very large canvases, particularly the enormous bouquets of sunflowers. You know that the Japanese instinctively look for contrasts and eat sweet peppers, salted candy, fried ices and iced fried things. So it follows, according to the same system, that in a large room there should only be very small pictures and in a very small room one should hang very large ones. I hope the day will come when I shall be able to show you this beautiful country here.

I have just finished a canvas representing the interior of a night café illuminated by lamps. A few poor night wanderers are asleep in a corner. The room is painted red, and there under the gaslight the green billiard table casts an immense shadow on the floor. There are 6 or 7 different reds in this canvas, from blood red to delicate pink, contrasting with as many pale or deep greens. I sent Theo a sketch of it today which is like a Japanese crepe print.

Theo wrote me that he had given you Japanese pictures. This is surely the practical way to arrive at an understanding of the direction which painting in bright clear colours has taken at present.

For my part I don't need Japanese pictures here, for I always tell myself that here I am in Japan. Which means that I have only to open my eyes and paint the effect of what is right in front of me.

Have you seen a very little mask of a smiling fat Japanese woman at Theo's? It is surprisingly expressive, that little mask. Did you think of taking a painting of mine there for yourself? I hope so, and I am very curious to know which one you chose. I am inclined to think that you took the white cabins surrounded by green plants under a blue sky, which I made at Saintes-Maries on the coast of the Mediterranean.

I ought to have gone back to Saintes-Maries again, as there are now people on the beach. But never mind, I have such a lot to do here. At present I absolutely want to paint a starry sky. It often seems to me that night is still more richly coloured than the day; having hues of the most intense violets, blues and greens. If only you pay attention to it you will see that certain stars are lemon-yellow, others pink or a green, blue and forget-me-not brilliance. And without my expatiating on this theme it is obvious that putting little white dots on the blue-black is not enough to paint a starry sky.

My house here is painted the yellow colour of fresh butter outside with raw green shutters; it stands in the full sunlight on a square which has a green garden with plane trees, oleanders and acacias. And it is completely whitewashed inside, and the floor is made of red bricks. And over it the intensely blue sky. There I can live and breathe, think and paint. And it seems to me that I might go farther into the South, rather than go back up to the North again, seeing that I am greatly in need of a strong heat, so that my blood can circulate normally. Here I feel much better than I did in Paris.

You see, I can hardly doubt that you on your part would also like the South enormously. The fact is that the sun has never penetrated us people of the North enough.

It is already a few days since I started writing this letter, and now I will continue it. In point of fact I was interrupted these days by my toiling on a new picture representing the outside of a café at night. On the terrace there are the tiny figures of drinkers. An immense yellow lantern illuminates the terrace, the façade and the sidewalk, and even casts its light on the pavement of the streets, which takes a pinkish violet tone. The gables of the houses in the street stretching away under a blue sky spangled with stars are dark blue or violet with a green tree. Here you have a night picture without black in it, done with nothing but beautiful blue and violet and green, and lemon-yellow. It amuses me enormously to paint the night right on the spot. They used to draw and paint the picture in the daytime after the sketch. But I find satisfaction in painting the thing immediately.

Of course it's true that in the dark I may mistake a blue for a green, a blue-lilac for a pink-lilac, for you cannot distinguish the quality of a hue very well. But it is the only way to get rid of the conventional night scenes with their poor sallow whitish light, when even a simple candle gives us the richest yellows and orange tints.

I also made a new portrait of myself, a study, in which I look like a Japanese.

So far you have not told me whether you have read Bel Ami by Guy de Maupassant, and what in general you think of his talent now. I say this because the beginning of Bel Ami happens to be a description of a starlight night in Paris with the brightly lighted cafés of the Boulevard, and this is approximately the same subject I just painted.

Speaking of Guy de Maupassant, I want to tell you that I very much admire what he does, and I strongly urge you to read everything that he has written. You ought to read Zola, de Maupassant, de Goncourt as completely as possible in order to get something of a clear insight into the modern novel. Have you read Balzac? I am reading him again here.

My dear sister, it is my belief that it is actually one's duty to paint the rich and magnificent aspects of nature. We need gaiety and happiness, hope and love.

The more ugly, old, mean, ill, poor I get, the more I want to take my revenge by producing a brilliant colour, well arranged, resplendent. Jewellers too get old and ugly before they learn how to arrange precious stones properly. And arranging the colours in a painting in order to make them vibrate and to enhance their value by their contrasts is something like arranging jewels properly or designing costumes. You will see that by making a habit of looking at Japanese pictures you will love to make up bouquets and to do things with flowers all the more. I must finish this letter now if I want to get it off today. I shall be very happy to have the picture of Mother that you speak of, so don't forget to send it to me. Give my dearest love to Mother, I often think of you two, and it pleases me very much that you know our life a little better now.

I'm afraid Theo will feel too lonely now, but he will be visited by a Belgian impressionist painter one of these days, the one I told you about at the beginning of this letter, and who is going to spend some time in Paris. And there will be a lot of other painters who will return to Paris with the studies they did during the fine season …

I embrace you and Mother.

Yours, Vincent

Arles, 26th December 1888

Monsieur Gogh,

I have been to see your brother Vincent. I promised to tell you what I thought of him. I am sorry to tell you that I think he is lost. Not only is his mind affected, but also he is very weak and despondent. He recognized me but did not show any pleasure at seeing me and didn't ask about any member of my family nor anyone else that he knows. When I left him I told him that I would come back to see him; he replied that we would meet again in heaven, and from his manner I understand that he was saying a prayer. From what the porter told me, I think that they are taking the necessary steps to have him placed in a mental hospital.

Please accept, Monsieur, the greetings of him who calls himself the friend of your beloved brother.

Roulin, Joseph.

Entrepeneur des Postes

Rue de la Montagne du Cordes, 10

Arles sur Rhone

My family sends their greetings to M. Paul Gauguin.

Arles, 29 December 1888

Monsieur,

I hasten to respond to your letter and to give you the latest on the state of your brother.

I will first of all tell you that it is very difficult to definitively answer all the questions that you ask me. I will, however, give you my personal appreciation. The Protestant pastor M. Salles came to find me this evening, and we went to visit him. He was very calm and it appeared that all was well. When he saw me entering his room he told me that he wanted to have the least possible contact with me. Without a doubt he thought it was I who had locked him up. I have assured him that I am a friend to him and I want to see him well again very soon. I didn't hide the situation from him and explained to him why he was isolated in a room. I told him that his attacks didn't allow us to let him in the wards among our other patients. We talked a good while and we parted as good friends. He begged me to write to you and give you all the news; something he wouldn’t have done at the start of our interview. When I tried to talk to him about the motive that had driven him to cut his ear; he answered me that it was quite a personal business.